Americanicity – Photographs by John G. Zimmerman

Visitors to this exhibition will experience Mr. Zimmerman’s photojournalism transformed from the covers and pages of Time, Life, Ebony, and Sports Illustrated magazines to framed prints in the Art Intersection North and South Galleries.

Heartfelt gratitude to Linda and Darryl Zimmerman of the John G. Zimmerman Archive for their collaboration to create this special exhibition bringing a perspective of American life through the breadth, innovation, and impact of Mr. Zimmerman’s photography.

Photographer John G. Zimmerman poses for Hawk or Dove, experimental series on political cliches, New York City, 1970.

Virtual Tour of Americanicity

This virtual tour through Americanicity in the Art Intersection Galleries lets you share the exhibition space with your friends and family that can’t visit us in the Gilbert Heritage District. Take a closer look at the individual images in the gallery below.

Cleaning the Stars and Stripes, Detroit, 1954

The images from John G. Zimmerman, a photographer and innovator, bring into view the lives and lifestyles of American families, politics, sports, and society from the 1950s through mid-1970s. This golden era of the Fourth Estate, before the internet and cable news, when photojournalism projected influence through print media, newspapers, magazines, and billboards into our homes and businesses, informed social behavior, personal knowledge, and political policy.

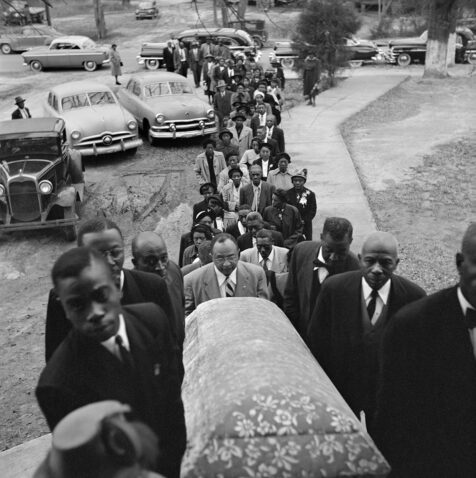

Funeral Procession, Sandersville, Georgia, 1953

Members of Congress on the Steps of the U.S Capitol. Washington D.C. 1951

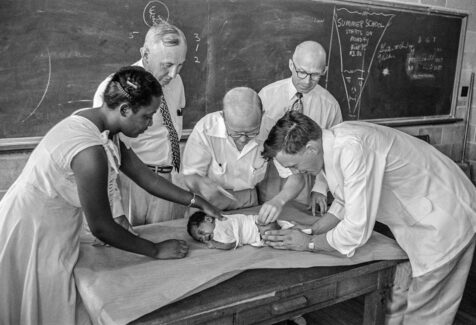

Americanicity seeks to bridge the photographs of John G. Zimmerman illustrating American social, political, and lifestyle from the mid-twentieth century to the recurrence in today’s contemporaneous news and lifestyle. His images bring into view the patriotic symbol of the American flag, distribution of a new polio vaccine in the African American community, the first televised presidential inauguration (the most watched ever), portraits of political leadership, intimate family dinners, and life in American Black communities.

Watching Eisenhower’s inauguration on television, Atlanta, GA, 1953

Americanicity, images that message behavior, and politics unique to America occurred then and now have reoccurred, were constructed and now reconstructed; the corruption, celebration, disappointment, and racism visible during his tenure as a photojournalist recreated again in contemporary United States of America. Mr. Zimmerman covered the whole range of society and American culture (both the positive and negative aspects) with a consistent style and unique presence, visible in all of his images whether reportage, editorial, or commercial.

Vice President Richard Nixon at Young Republican Convention, 1955, Detroit

Defining moments of the mid-twentieth century were disseminated through the work of remarkable writers and photojournalists, while today the Fifth Estate of social media and the power of instant communication, shifts photojournalism to image capture on phone cameras. As a foundational figure in the observing, documenting, and commenting on American society and culture, Mr. Zimmerman constructed the foundation for the way we all document, appreciate, and critique America today through our phone cameras.

Polio Vaccination, Montgomery Alabama, 1953

Biography

Early in the 1950s a correspondent for LIFE magazine received an assignment to cover a story with a new free-lance photographer named John G. Zimmerman. “How will I know which photographer is Zimmerman?” asked the correspondent. ”Just look for the guy who is screwing his equipment back together,” answered his editor. The anecdote captures Zimmerman’s life-long fascination with camera technology. Making pictures for magazines such as LIFE, Sports Illustrated, Saturday Evening Post and Time as well as commercial work for over four decades, Zimmerman consistently created photographs known for their innovation and artistry.

Growing up in Torrance, California, Zimmerman joined a photographic club in junior high school and spent afternoons developing film with friends in their mothers’ kitchens. Zimmerman’s father, John L. Zimmerman, was a gaffer at a major film studio and further encouraged his son by building a darkroom at home. John G. credited early exposure to his father’s craft in part for his ability to engineer cameras and lighting to his own designs.

Zimmerman’s formal training began with a three-year photography course at John C. Freemont High School in Los Angeles. Taught by Hollywood cinematographer Clarence A. Bach, the intensive program was famous for launching the careers of no less than six LIFE photographers. Bach handed out photo assignments as if he were the editor of a daily newspaper; his students had to be prepared to cover any assignment whether it be a sporting event or an entertainer at a local nightclub. The teenage Zimmerman photographed Bing Crosby and Nat King Cole and made up 11 x 14 prints in his lab, selling them to the singers for $1.50 each.

Zimmerman often cited his early training under Bach as a significant influence in his career. Bach encouraged his graduates to provide guidance to younger photographers just starting out, something that Zimmerman practiced throughout his career and which distinguished him in the competitive world of professional photography. His relationships with fellow Bach graduates, including Life photographers Mark Kauffman and John Dominis, were life-long.

Julie Nixon looks through hole in Berlin Wall, Berlin, W. Germany, 1963

Upon graduating high school, Zimmerman enlisted as a Navy photographer and served briefly. With the help of Bach’s informal alumni network, Zimmerman landed his first job as a staff photographer at the Time bureau in Washington D.C. His first assignment as a Time staffer in 1950 demonstrated a combination of quick thinking and sheer luck. Leaving the White House just as Puerto Rican nationalists attempted to assassinate President Truman, Zimmerman was among the first photographers on the scene. His photos of the assault were featured in both Time and LIFE.

From 1952-1955, Zimmerman photographed a series of assignments for Ebony depicting the lives of African Americans in the Midwest and the Jim Crow south. These photographs are a lesser-known yet notable part of Zimmerman’s early work. The subject matter ranges from the first all black supermarket in Detroit, boxing legend Joe Louis, to sharecropper Matt Ingram’s quest for justice.

Department Store Ride, Yanceyville, North Carolina, 1953

While the Ebony assignments are straight-forward photojournalism, Zimmerman also created pictures during this time that pushed the boundaries of photojournalism. In 1955, LIFE assigned him to document Detroit’s old Mariners’ Church being moved to a new location across town. The move took four weeks to complete yet Zimmerman created a photo that gives the effect of the church hurtling through downtown Detroit at top speed. The use of technology to show on film what the naked eye could never see became a hallmark of Zimmerman’s mature work.

Sports Illustrated, 1956-1963

Zimmerman’s innovative approach caught the eye of Gerald Astor, Picture Editor of the newly formed Sports Illustrated. Astor hired him in 1956 as one of the magazine’s first staff photographers. While at the magazine, Zimmerman created many memorable images such as Bednarik Knocks Out Gifford (1960) that have become icons of sports photography. But it was his unique camera placements and electronic lighting techniques, combined with his pioneering use of remote controlled cameras, motor-driven camera sequences and double shutter designs that revolutionized how sports were viewed.

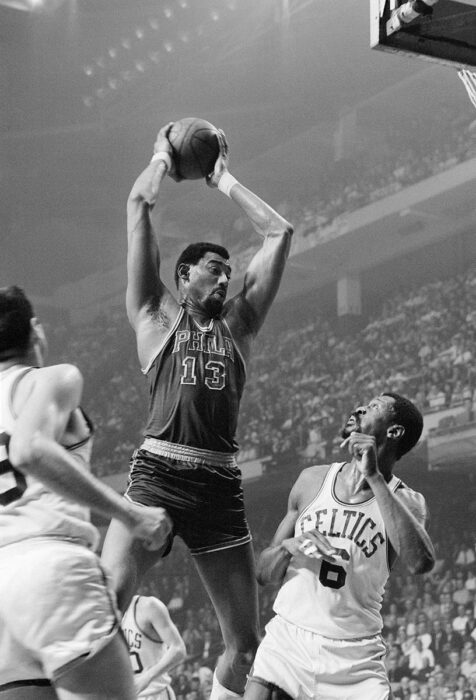

Wilt Chamberlain vs Bill Russell, NBA Playoffs, 1967

To bring readers up close to basketball, for example, Zimmerman put remote-controlled cameras on the glass backboards. Sports Illustrated photographer Walter Iooss Jr. recalled seeing Zimmerman’s 1961 photographs of basketball star Wilt Chamberlain: “it was the first time a photojournalist had placed a camera above the rim of a basket. It was like looking at something from another planet.” Many of Zimmerman’s techniques are commonplace today but were unheard of when he first used them.

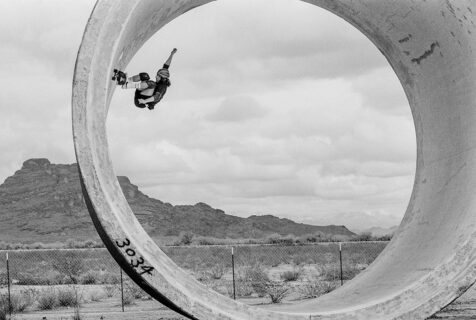

Tony Alva skateboards in the Arizona desert. 1978

Zimmerman travelled incessantly as a staffer for Sports Illustrated. It was on one of his many flights, an 83 minute connection between New York and Philadelphia, that he met his future wife, a dark-haired TWA stewardess named Delores Miter. They were married in 1958 and had three children. During those years, Delores became her husband’s business partner and eventually assumed management of all the company finances, leaving Zimmerman free to focus on his photographic work.

Casey Stengel, manager of the New York Yankees, interviewed after winning game 7 and series vs Milwaukee Braves, Milwaukee, 1958

Editorial and Commercial Work, 1964-1991

Zimmerman left Sports Illustrated in 1963 to work for the Saturday Evening Post, a move motivated primarily by a desire to widen his knowledge of the craft. Though short-lived, his work for the Post (1963-65) covered the gamut of American popular culture—from the Beatles’ appearance on Ed Sullivan in 1964 to the latest in fashion, entertainment, politics, business and science.

Introducing the 1956 Ford Lincoln, Detroit, 1955

After moving to Los Angeles with his family in 1972, Zimmerman broke new ground by taking on commercial work, using his technical expertise to illustrate complex concepts for advertising clients such as Ford, Exxon, G.E. and Coca Cola among others. He also employed his elaborate lighting setups to become a sought-after architectural photographer for publications such as American Home and Time Life Books. He continued to cover sports throughout his career, photographing ten Olympic Games and over one hundred Sports Illustrated covers, including seven of the ever-popular swimsuit issues.

“John was a master of lighting, whether the subject was a 20,000 seat arena or Christie Brinkley on a beach,” recalled photographer Neil Leifer in a 2002 tribute. “He was at ease shooting in 35mm or large format, as adept with wide-angle lenses as he was with telephotos. I put him up there with Avedon, Leibowitz, Penn and Adams.”

Posted in | No Comments »